Lullabies of Broadmoor - A Broadmoor Quartet at the Finborough Theatreby Steve Hennessy Stepping out Theatre in association with

Chrysalis and Simon James Collier |

Venus at Broadmoor The Demon Box The Murder Club Wilderness

FINBOROUGH REVIEWSThe Times by

Sam Marlowe Strychnine-laced

chocolates, a razor, a rolling pin: the instruments of death scattered through these four

real-life crime stories often have an apparent ordinariness that belies their sinister use

by a murderer. Steve Hennessy’s quartet of plays, which range in setting from the

late 19th century to the 1920s, hint at the traditions of the Victorian musical hall and

melodrama, a flavour enhanced by Ann Stiddard’s design, with its faux-gilt proscenium

arch. But if the four dramas ooze violence, they are thoughtful, compassionate and

fascinating, too... superbly acted by a role-swapping, four-strong cast. Love,

obsession, thwarted creativity and deep psychological damage recur as we are introduced to

a succession of inmates at the famous institution for the criminally insane by John

Coleman (Chris Donnelly), an attendant in Broadmoor’s “gentlemen’s

block”. In Venus of Broadmoor, we hear how Christiana Edmunds (Violet Ryder),

rejected by her married lover, took to poisoning chocolate creams, resulting in the death

of a young boy; in The Demon Box, the painter Richard Dadd (Chris Bianchi), who killed his

father, and the American Dr William Chester Minor (Chris Courtenay), traumatised by the

Civil War in his home country, collide over set decorations for a Broadmoor dramatic

production; Richard Prince, a failed actor who stabbed a successful rival out of bitter

envy, meets the charismatic conman Ronald True, killer of the Finborough Road prostitute

Olive Young, in The Murder Club; and Wilderness returns to the Minor case to trace the

murderer’s psychosis back to its shocking source. Hennessy’s

writing is playful and profound. The ghosts of victims rise up to describe their fate;

figures from biblical, Greek and Egyptian mythology are invoked, propelling the tormented

into atrocity. And the bloody business of politics and imperialism seeps into acts of

individual slaughter: Blanche Marvin’s London Theatreviews

The concept of a quartet of plays centred on actual case histories of the insane at Broadmoor is fascinating not only because of the inmates but also in the causes of madness and the actual conditions at Broadmoor in the late 19th-century. The poor were kept under dire circumstances, the rich in private cells with the poor inmates serving them. They had a theatre, entertainment and expensive liquor. We are confronted with five notorious murderers and five victims, some repentant others unaware of their crime. These are Gothic plays of murder, love, obsession, responsibility, and redemption directed with delicacy and sensitivity to the crimes committed while recreating an atmosphere of both period and place. Carefully designed to transfer from one inmate’s cell to another yet it maintains an overall feeling of Broadmoor while the lighting effects, soundscape, and movement are kept to its specific style. It is beautifully performed by the four actors changing from role to role without being theatrical. One is deeply moved by the countless relaying of pain and anguish suffered by both murderer and victim. The actual period becomes relevant to the crime as the victims reproduce their cruel memory of suffering whether alive or as ghosts. It is a distressing but at the same time a compelling concept where the production itself serves to evoke the deeper feelings within the torment of people. The four actors evolve from each character with honesty in their portrayal and bring an overall continuity to the production. It is one of those rare moments in theatre where it all jells into a complete whole. Import import and export for radio, foreign festivals, or Off Broadway. Venus at Broadmoor/The Demon Box by Paul Vale Lullabies of Broadmoor is a quartet of single act plays examining some of the more notorious inmates of Broadmoor prison during the late 19th and early 20th century. Steve Hennessy’s plays are performing in rep throughout September and, although they can be seen in any order, it is recommended that Venus at Broadmoor and The Demon Box be seen first. The evening is vaguely reminiscent of the episodic Amicus horror movies from the early seventies with homicidal insanity as a theme. Thankfully there are elements of sanity to ground the audience, not least a strong central performance by Chris Donnelly as the Principal Attendant who goes someway to act as narrator to the plays as well as playing an integral part in the stories. Venus at Broadmoor is in fact Christiana Edmunds, the notorious Chocolate Cream Poisoner, whose random career resulted in her admittance to Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum in 1870. Violet Ryder is a seductive, perky Edmunds, so completely in denial of her actions as to be deeply moving and yet genuinely horrifying. The Demon Box centres on the broken personality of the great Victorian artist Richard Dadd. Admitted after murdering his father, Dadd’s tale invokes the mysteries of ancient Egypt and details his refusal to help fellow inmate, Dr William Chester Minor rehabilitate. Sad-eyed Chris Bianchi is superb as Dadd, negotiating the rich subtext of his insanity with subtlety and understanding, but it is the final image of Chris Courtenay as an unhinged Minor, dribbling paint, which really sticks in your mind. The Murder Club/Wilderness by

Paul Vale In

the second part of this quartet of plays set in the infamous Written

in a much stronger, more fluid style much of The Murder Club is narrated by the spirit of

Olive Young, a prostitute and resident, coincidently of 13, In

Wilderness we meet William Chester Minor, a surgeon during the American Civil War,

imprisoned in Broadmoor indefinitely for the murder of George Merrett. Minor, played with

conviction by Chris Courtenay seeks redemption initially through his work but eventually

invites Merrett’s wife, played by the adaptable Violet Ryder, to the hospital to

offer money and an apology of sorts. Mix into this piece the ghost of Merrett and Coleman,

Broadmoor’s long suffering attendant, and we discover that it is not only those

locked away that seek atonement. Author Steve Hennessy has created a cycle of morality plays for the modern psyche - a steady, occasionally witty, yet stylised quartet of plays that are eminently watchable, deeply moral and yet refuse to preach or exact any retrospective reform. Director Chris Loveless has motivated an expert cast into creating a deeply irregular and relatively unexplored territory inhabited with spirits, demons and monsters both metaphysical and otherwise.

by

Michael Stewart Is

the title suggests images of Busby Berkeley-style babes hoofing it up, banish the thought.

There is nothing soothing or glitzy in Steve Hennessy's quartet of gruesome plays

revolving around some of the more notorious inmates of the Broadmoor mental institution. The

four protagonists are Hennessy

ingeniously mixes and matches these grisly events and damaged people, revealing fresh

insights into morality and madness -and the occasional madness of morality. Linking all

four plays is the narrator John Coleman, a warden-attendant who himself is struggling with

his own form of insanity - the demon drink. Indeed

demons, deities and spirits of all kinds haunt these plays. Osiris the Egyptian god

appears to Dadd while on a trip to the Nile and instructs him to return to Reprieved

from the hangman's noose, Dadd, Prince and True found redemption in creativity and became

bulwarks of Broadmoor's theatrical and musical productions. Minor's saviour is the power

of words and he became one of the major contributors to the Oxford English Dictionary. If

Dadd had gone to the gallows, his incredibly detailed masterpiece The Fairy Feller's

Master-Stroke would have been lost. Ostensibly

a fairy tale, it could easily be read as a microcosm of Broadmoor's weird denizens. It's

to Hennessy's credit that he manages to seamlessly integrate all these themes and

allusions. A particularly striking moment is Churchill urging troops to bomb and gas

innocent Iraqi villagers which points up real madness, that of war. Actors

Chris Bianchi, Chris Courtenay, Chris Donnelly and Violet Ryder all deserve a gong for

their faultless work in portraying such a large and challenging cast of characters. by Lori Hopkins My expectations were high as I arrived at the Finborough Theatre for a mammoth theatre experience; a quartet of plays recommended in Lyn Gardner’s ‘What to See this Week’ at a theatre venue that has won numerous awards including Fringe Theatre of the Year 2010. Steve Hennessy’s Lullabies of Broadmoor has just returned from the Edinburgh Fringe to the kooky-yet-chic Finborough Theatre, where Hennessy was writer-in-residence from 2004-2006. Hennessy originally wrote Wilderness back in 2002 and had no idea that nearly a decade later he would have written a further three episodes to complete his Broadmoor Quartet. Set in Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, the plays are based on the true stories of five of the inmates from the late nineteenth through to early twentieth century. The plays themselves are each dedicated to the victims of the inmates’ crimes. The quartet kicks off with the most recently written, Venus of Broadmoor, telling the tale of Christiana Edmunds, ‘The Chocolate-Cream Posioner’. The set-up for this and the preceding three plays involved the four actors performing a physical score on a loop. The subtle repeated gestures and movements began to give an insight into each character and were performed with absolute precision and clarity. Ten minutes of repetition left me almost bursting with anticipation, and the play did not disappoint. Principal attendant John Coleman (Chris Donnelly) is the constant element throughout the four plays. Venus of Broadmoor begins with a monologue by Coleman, brimming with nervous excitement. His level of focus and engagement remained throughout the quartet. We see Coleman on a torturous journey as he tries to “stay on the wagon” and resist his inappropriate lusting for the murderer Christiana Edmunds. As this first piece unravels it soon becomes clear that physical gesture and recurring motifs were to be crucial to the development of plot and character. Clever choreography was used to suggest props, people and scenery that allowed the audience to open their imaginations and be taken on a journey. The second offering, The Demon Box, introduced the artist and murderer Richard Dadd and ex-surgeon Doctor William Chester Minor. The Demon Box imagines that these two criminals are forced together to work on painting the backdrop for the Broadmoor Theatre. Both men are deeply troubled by their past and Hennessy interweaves their tales with that of Ariel and Prospero from The Tempest and the Egyptian myth of Osiris and Isis. The Demon Box shows us many different perceptions of the same characters, and gives an interesting view on the treatment and attitudes towards mental health at the turn of the century. There were some beautiful links back to the first play both in the form of textual repetition and in gesture. The final words of the first play, “light . . . and air . . . and clouds”, are echoed by Ariel several times so that although each play is self-contained there is a lovely feeling of continuity, almost like episodes of a dark soap opera. Play number three, The Murder Club, is driven by a central character, the feisty ghost of murdered prostitute Olive Young (Violet Ryder). With a slightly modern feminist edge, Olive has the power to freeze and play with the action on stage with a mere click of her fingers. The audience is immediately drawn to like her with witty one-liners such as “there are too many todgers in the world”. Unfortunately, however, Olive does not possess enough power to actually change the course of events and has to watch as her killer torments and manipulates his fellow inmates and the attendant Coleman. The Murder Club has a rather self-referential feel as Broadmoor’s Social Club is planning on putting on a play, a play that just so happens to be a direct re-telling of the murder carried out by failed actor Richard Prince (Chris Courtenay). The sadistic Ronald True, (Chris Bianchi) uses emotional blackmail to torture Prince, and Bianchi’s creepy portrayal left me feeling sick to the stomach. The fourth and final instalment, Wilderness, was littered with clever echoes of the previous three plays and the return of Doctor William Chester Minor who features in The Demon Box. Minor is overcome with remorse for his crime and strikes up an unlikely friendship with his victim’s widow when he offers her money to compensate for the murder of her husband. Possibly the most difficult to watch, Wilderness tears our allegiances between the characters as the attendant Coleman has succumbed to his drink addiction and appears to be losing his sanity, and Minor is clearly on an emotional rollercoaster and bound to snap at any minute. It is cleverly written so that we don’t really know who to believe at any given moment. There is a great moment where Minor talks as if possessed by the ghost of his victim, but is sharply reprimanded by the widow who points out that he couldn’t possibly be her late husband as he would never use foul language. The quartet climaxes in a gruesome act of violence that left the gentlemen in the audience crossing their legs and squirming in empathetic pain. The cast and direction of this show were absolutely brilliant, from the flexibility of the actors to take on so many roles to the physical precision and complicity. Hennessy’s excellent use of language make Lullabies of Broadmoor a real treat for the young-at-heart as this production is storytelling for adults at its very best. Tim Bartlett’s flawless lighting design played a key part in distinguishing fantasy from reality and dream from hallucination. All-in-all this play deserves sell-out performances every evening. The opportunity to see four plays in a day is a rare but exciting treat and I would highly recommend giving it a go. Venus at Broadmoor/The Demon Box

The Finborough

(small, dark and plush) is the perfect setting for Steve Hennessy’s excellent quartet

of dark comedies – the focus of this review being Venus at Broadmoor and The Demon

Box. The first is a tragic melodrama of love

and loss, the second a more sinisterly spiritual exploration of madness which draws upon

the events of the first to further flesh out characters and draw you further into the

world of Broadmoor. Steve Hennessy’s script is tricky – that is not to say it is

bad; quite the opposite. However it is a credit to the director Chris Loveless and his

cast of four that the material is handled with such skill. Knowing full well that,

particularly in such a small space, the portrayal of madness in the late 1800s could prove

awkward and (worse case scenario) embarrassing the company works wonders – using some

tricks of the Victorian melodrama trade to both emphasise the extraordinary circumstances

and flesh out the entirely ordinary human conditions. Both shows

begin with a nice piece of physical trickery. The actors take their places about the stage

and engage in menial tasks – reading a penny dreadful, powdering, opening a letter

and so on. The music is foreboding and the lighting imposing giving the feeling that all

is not well even while the audience makes its apologetic entrance. The movement is well

choreographed- a statement true of the entire piece- with the characters stuck like a broken record in the routine of movement

until the play begins (reading a penny dreadful, powdering, opening a letter and so

on…) When Venus at Broadmoor begins, kicking off the double bill, the audience is

guided through the story by John Coleman – a principal attendant at Broadmoor whose

desire to fully understand the patients and their conditions leads to unwise and often

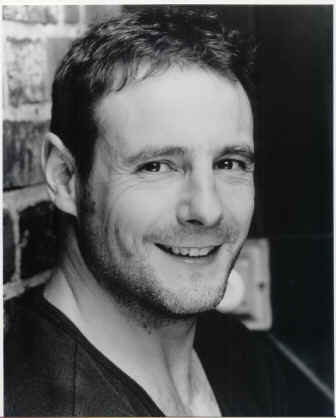

harmful emotional bonds. Chris Donnelly plays the part with such subtlety, tenderness and

honesty that the audience is immediately attached to him; ready to forgive him anything

(including a fairly creepy late night encounter) and willing to believe anything he says.

His descent into an ill-advised love affair in Venus at Broadmoor has the heart beating

fast and the fists clenched ready to punch the air when it all turns out well. Such a

shame, then, that it doesn’t. The beguiling

Violet Ryder is utterly convincing as Christiana Edmunds -the object of everyone’s

desires; she makes the character likeable enough to let the audience warm to her, yet

irritating enough to wish better things for the lovely Coleman (the fact that she drives

him to drink is infuriating.) You do feel for her though, which is again a testament to

Ryder’s skill and Loveless’ wise choice to cast an actress that is inherently

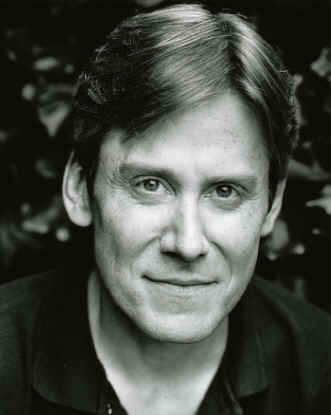

likeable. Credit must also be given to the charismatic Chris Courtenay for his slippery

performance as Christiana’s lover Dr. Beard. He inhabits the more melodramatic world

of the play, where emotions manifest themselves as physically more stylised and eccentric. This is a wise choice,

since it would be imposing and uncomfortable to deal with some of the issues in these

sections naturalistically. It also allows Coleman to view the flashbacks as something

separate from himself and gives his moments of gravitas more integrity. Chris

Bianchi... comes to the fore in the second of the two pieces, the Demon Box. As the

reclusive artist Richard Dadd (imprisoned at Broadmoor for the murder of his father)

Bianchi is likeable, loathsome, human and baffling. He gives the character a gentleness

that makes his violence oddly more understandable and his final betrayal utterly

heartrending. Chris Courtenay is again excellent as the desperate American apprentice to

Bianchi (with a very convincing accent, which is always a bonus) whose final breakdown

offers a good lesson in how to pitch stage madness in a small space. Donnelly is once

again enchanting as Coleman, offering more insight into the character we grew to love in

the first encounter and allowing the audience to reflect on what they’ve already seen

and know. Ryder has a very tricky task in this piece. If Christiana’s madness was

represented by melodrama, Richard Dadd’s is all about spirits and ancient Egypt

– an altogether more difficult thing to achieve on stage and something for which

Ryder is largely responsible. It is done well, with particular credit due to the lighting

designer Tim Bartlett... both pieces are highly recommended and offer very few weak links

in the midst of a thoroughly enjoyable evening. The Murder Club/Wilderness Steve Hennessy’s two one-act

plays are performed as a double bill under the collective title of Lullabies of Broadmoor. The Murder Club is about actor

Richard Prince who killed matinee idol William Terriss as he was about to enter the

Vaudeville Theatre’s stage door in 1897. He killed him because he was

jealous of his talent and convinced he was doing everything to stop him getting work. He

is joined by another murderer, Ronald True, who thinks it is grossly unfair to be

incarcerated for killing a prostitute when it’s all right for the British army to be

killing hundreds of civilians in Wilderness, which is even more

impressive, is set in the 1870’s and is about Dr William Chester Morris, who was a

surgeon serving in the Union army during the American Civil War. Traumatised by the

horrific things he had seen on the battlefield he came to Chris Courtenay’s performance

as Morris is notable for its sensitivity. There are also good performances by Chris

Bianchi as the ghost, Violet Ryder as the widow and Chris Donnelly as the humane prison

attendant. The Murder Club and Wilderness are

part of a quartet of one-act plays about insane murderers by Hennessy and they are

alternating with a double-bill of Venus at Broadmoor and The Demon Box. by Howard Loxton These four plays, presented as two separate double bills, are all set in the criminal lunatic asylum opened in 1863 and since 1948 known as the Broadmoor Hospital. They are set at different periods from 1872 to 1922 and feature five of some of the institution's most prominent prisoner patients. Each play centres on the story of one particular murderer and their victims with some characters recurring in other plays, especially warder John Coleman, principal attendant on the Broadmoor staff who acts as narrator to three of the plays as well as being part of the action. Chris Loveless' production deftly interweaves the strands of present-tense, flash-back, ghosts, hallucinations, horrific imagination and patches of poetic imagery. He starts each play in the same way: with all the characters on stage as the audience takes its seats. To a repetitive music track which swells and recedes in volume they each repeat their own cycle of action many times to the point where you can't help but feel the weight of the seemingly endless chain of days of their confinement. Venus at Broadmoor, set in the summer of 1872 gives us the story of Christiana Edmunds, the "Chocolate Cream Poisoner" as she was dubbed by the press, who, when her married lover decided to break off their relationship, attempted to poison his wife with a gift of chocolates laced with strychnine. They made her ill but didn't kill her. However in the following year Edmunds obtained chocolates to which she added poison then returned them to the shopkeepers, leading to an outbreak of poisoning in Brighton, which included the death of a little boy on holiday, four year old Sidney Barker. But neither this, nor any of the other plays, is just about a murder: they give a picture of the nature of madness in its different forms, touch on ideas about its treatment and explore what might tip individuals into psychotic unbalance. They are not concerned only with the inmates for everyone in these plays has issues and problems they find difficult to face. Venus at Broadmoor introduces the character of Coleman, sitting on duty reading a 'penny dreadful' and taking an occasional tipple from the flask he should not be carrying. I don't know whether Coleman is an actual historical person (everyone else in these plays certainly is), but Chris Donnelly makes him a very real one, as easy in his contact with the audience as he is caring of those in his charge. "What," asks Coleman, "is the cure for love?" for he becomes obsessed with Miss Edmunds, whose madness seems linked with nymphomania. She turns her wiles on Dr Beard, the compassionate Medical Superintendent at Broadmoor whose kindness and belief that talking to patients to make them understand their crime will help towards a cure is dismissed as sentimental by his medical peers. Then there is her ex-lover with his guilt to hide. The Demon Box is set in the same period and introduces the painter Richard Dadd and William Chester Minor, a lexicographer and former surgeon during the American Civil War. Dadd is famous for his extraordinarily detailed paintings, especially those of fairies. Dadd had already spent twenty years in Bedlam before being moved to Broadmoor, and in 1872 redecorated of the theatre there, including painting a drop cloth for the stage. On a painting tour in the Middle East, he had developed an obsession about the Egyptian god Osiris and, believing it to be at the god's instruction, had killed his father. Dadd seems to have a companion spirit based on Shakespeare's Ariel (though played by the same actress in the same costume there is a hint that this delusion might be linked with 'Venus' Edmunds). Dadd's is an imagination that sometimes breaks its bounds into fits of madness. Dr Minor, who is haunted by his Civil War experiences, which are at the centre of the final play of this quartet, has recently arrived and, since he is interested in both theatre and painting, Coleman thinks he may be able to help Dadd with the redecoration which is taking far too long, but Minor seems to become part of Dadd's paranoia. What was intended as part of the socialising that improves the life of the inmates goes terribly wrong and we begin experience something of what these men feel. The Murder Club presents two patients in 1922: failed actor Richard Prince who has already been there half a century and newly arrived conman Ronald True. Price was the killer of West End heartthrob William Terriss, True had battered a prostitute to death with a rolling pin, a murder committed just down the road from the theatre. This was a time when British Imperial forces were using aerial bombardment and probably poison gas to wipe out Kurdish opposition in Iraq, for Winston Churchill had certainly expressed himself "strongly in favour of using poisoned gas against uncivilised tribes". Who is mad and who is a murderer is a question the dramatist certainly raises but the emphasis here is on conman True's crime. The narrator for this play is Olive Young, the woman True killed. Sexually abused by her father and thrown out by her mother when she got pregnant, she tries to understand why she let her murderer in when she already didn't like him. Meanwhile True, who never acknowledges his crime, goes on conning whoever he can while baiting Prince, a pathetic figure, now conductor of the institution's incompetently amateur orchestra. Wilderness puts the clock back again to 1902, but the Wilderness of the title was a Civil War battleground in May 1864 where there were some 27,000 casualties, including many men burned in a forest fire. Minor is haunted by these memories and especially that of having to brand a young Irish soldier on the cheek with hot iron D as a deserter. Minor's crime was motiveless and accidental, in a delusion he thought he was being attacked by an Irishman and shot him, furnace stoker George Merrett whom we meet as a ghost along with his living widow who actually befriends Minor. Here we are presented with the very rational educated man, working over many years on his contributions to the Oxford English Dictionary, and at the same time lapsing into delusions of people breaking into his room and trying to poison him. Coming from a wealthy family and still getting an army pension, he has paid for a metal floor to be laid in his cell to prevent people coming up through the floorboards. This may all sound pretty grim, and indeed it is, but both production and playing have a light touch that leavens it with humour. The cast of four who appear in every play have an opportunity to show off their versatility and make these characters truly come to life. Chris Bianchi is a touchingly disappointed Dr Orange, a bewilderingly disoriented Dadd, a truly nasty True and an innocently uncomprehending Merrett; Chris Courtenay plays the hypocritical Dr Beard, still jealous Prince and gives a particularly fine performance as Minor, driven eventually to self-mutilation and Violet Ryder is flirtatious Christiana, the tantalising Ariel, a touchingly damaged and very honest Olive Yong and as Mrs Merrett we can see here trying to understand her own behaviour. Chris Donnelly's role stays the same but he is beautifully in character. A suggestion of a gilded gothic proscenium arch and red drapes which suggest both Victorian opulence and the theatrical framework of the piece give a richness to what is otherwise a very simple staging by Ann Stiddard that throws the emphasis on the performers, carefully costumed by Rebecca Sellors (Christiana, for instance, in period underwear) and dramatically lit by Tim Bartlett. It takes a bold designer to just throw a cloth over things she doesn't want us to see but you can get away with it in this intimate theatre and when interest is so focused on the performers you rarely notice what is behind them. Madness

and murder skilfully dissected. Now coupled in repertory

with two further plays about the asylum for the criminally insane, this is a new

production of two plays originally shown at the Finborough in 2004, with one actor and the

lighting designer the same. And, of course, the playwright – Chris Loveless’s

2011 revival reinforces its predecessor in showing Steve Hennessy has a true dramatic

instinct for constructing a story and stage images that infuse an atmosphere, and dramatic

speculation, in audience imaginations. Loveless

maintains tension throughout the plays’, and characters’, revelations and

deception. There’s decent playing, with Violet Ryder giving Olive a particular

pathos, while Chris Bianchi is forceful as the illusory Merrett and suavely manipulative

as the falsehood-filled True. These

new plays in what’s now a Broadmoor quartet take events back to the early days of

this asylum for the criminally insane. And of warden John Coleman, less inured to the ways

of madness and capable of being caught up with the attractions of ‘chocolate-cream

poisoner’ Christiana Edmunds. He’s partial to the sweets himself, as a means of

distraction from the alcohol with which he struggles through his career. Chris

Donnelly’s dutiful warder sullenly makes the point no-one cares for him, because he’s

not murdered anybody. And, as the powers-that-be investigate a cure for madness, Coleman

finds himself facing disciplinary action if he steps out of line. Madness

infiltrates events, real or imagined, in these plays, and Ann Stiddard’s

claustrophobic sets, taking up much of the Finborough’s limited spaced, emphasise the

trains of madness. In Edmunds, and artist Richard Dadd, painting the Broadmoor theatre’s

curtain in such detail the place can’t be used to put on plays. Dadd’s murderous

visions summon up an Ariel who deludes and eludes. Violet

Ryder, light as Ariel, is flighty as Christiana. Chris Courtenay's character, central in

Wilderness, is here an aspirant apprentice to the reluctant Dadd. And

Chris Bianchi is impressive both as the asylum boss who falters from certainty to drink

and disappointment when his curative ideas are rejected, and especially as Dadd, in whom

quiet certainty on the surface hides anxiety and anger as imagined demons invade his mind.

Dadd’s apparent sane confidence and authority can shift in a moment to unreasonable

anger or the pained intensity of imagined fears. Chris

Loveless directs with as sure a sense as in the other pairing. And, mainly, Steve Hennessy’s

scripts offer rich opportunities for actors and a rewarding experience for audiences, in

their purposeful ambiguities and whirl of words and action. Though this pair, with its

chronologically earlier events (the four are based on actual Broadmoor inmates) is

recommended for viewing first, I saw them the other way round and that has its own

fascinations – such as seeing warder Coleman more fully revealed; and, anyway, the

‘later’ plays were in fact written first. by Julia Rank In Steve

Hennessy’s Lullabies of Broadmoor, a quartet of plays set in the Broadmoor Criminal

Lunatic Asylum in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this notorious

establishment perhaps comes across as not being quite as horrific as one might imagine,

especially for the privileged ‘gentleman’ patients. There was an annual ball, a

theatre and an orchestra, and a certain amount of privacy with the luxury of a cell of

one’s own filled with personal knick-knacks (represented by Ann Stiddard’s

atmospheric design). One patient, a renowned scholar, is even allowed a penknife to cut

the pages in his books. Hennessy, who

has a background working in mental health, wrote Wilderness, the last play presented in

the sequence, in 2002 and was encouraged by Neil McPherson to write a second piece

featuring another well-known Broadmoor patient who committed a murder that took place on

the Finborough Road in 1922, and the double bill was produced by the Finborough in 2004.

The complete quartet (in which all roles are played by the same four actors) deals with

five of the most colourful patients who were reprieved from hanging on the grounds of

insanity, supervised by long-suffering middleman John Coleman, Principal Attendant of the

Gentleman’s Block, armed with his surreptitious hipflask of brandy. There’s a

mechanical quality to the pre-show tableaux performed to brooding music as if on a loop.

Prior to Venus of Broadmoor, a woman dressed in her corset and pantalettes powders her

nose and mimes a waltz with an invisible partner, a man toys with a bag of sweets and

another attempts to write a letter. Chris Loveless’s direction fully embraces the

referential nature of Hennessey’s writing, creating some visually arresting set

pieces. The first in

the sequence and the more recently written… is Venus of Broadmoor, dealing with the

case of Christiana Edmunds, dubbed the ‘Chocolate-cream poisoner’ in 1870 after

one of her randomly distributed poisoned chocolates killed a four-year-old boy on a day

out in Brighton. This pathologically coquettish young woman (after being subjected to a

traumatic description of death by strychnine, she changes the subject to the upcoming

asylum ball as if she hasn’t heard a word of it) bewitches Coleman into abandoning

all professionalism… Even more

meta-theatrical… is The Demon Box, paying homage to Shakespeare’s The Tempest

and Egyptian mythology. The murderer, the fairy painter Richard Dadd, who killed his

father believing himself to have been guided by the Egyptian god Osiris, is given the job

of re-decorating the Broadmoor theatre. During

this painstaking process, he is visited by the airy spirit Ariel, raising questions about

figments of the imagination and the dangers of ones that become too vivid. …The Murder Club is narrated by prostitute Olive Young, who was battered

to death with a rolling pin by serial conman Ronald True. While she can make acerbic

remarks about what she sees, she is helpless as her murderer charms and torments the other

patients. Her final speech as she recounts her final moments, the opposite of the

romanticised theatrical deaths that her negligent mother loved to weep over, is the most

touching moment in which theatricality and emotionalism combine. The final play

in the quartet Wilderness, telling the story of Dr William Chester Minor (who also appears

in The Demon Box) is possibly the strongest. Minor, a doctor, linguist, lexicologist (a

significant contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary) and arguably a genius, had the

dubious honour of being Broadmoor’s ‘show’ patient. He’s the only

murderer to show any remorse for what he has done, his intense self- loathing leading to a

gruesome denouement in his attempt to make amends. Damaged by his experiences as a surgeon

in the American Civil War and a painful loss of innocence during his childhood in Ceylon,

Minor moved to London and one evening shot George Merrett, a complete stranger, dead. When

Coleman remarks about Minor’s extreme act of self-mutilation, “How many of us

try that hard to be a better person?” one can’t help but agree. If my energy

began to flag somewhat, the impressively hardworking cast’s certainly didn’t.

Chris Donnelley, the only actor playing the same character throughout, successfully

communicates Coleman’s weariness and Violet Ryder is astonishing in all her roles: a

flirtatious Christiana, a mercurial and vicious Ariel, a heartbreaking Olive Young and an

earthy Eliza Merrett. Chris Bianchi is particularly skin crawling as the sleazily charming

Ronald True, with the audacity to treat Coleman like a friend and manages to get away it,

and Chris Courtenay gives an outstanding performance as Dr Minor, a fascinating character

who deserves an entire production to himself. by Jill Glenn Lullabies of Broadmoor, four linked

plays written by Steve Hennessy and directed by Chris Loveless, are now in performance at

the Finborough Theatre, London SW10. Weaving together the stories of five Broadmoor

inmates and their victims at the turn of the 20th century, these mini-dramas are funny and

sad by turns… clever, moving, thought-provoking. The Finborough is a seriously

intimate theatre, perfect for creating an immediate sense of claustrophobia, and

absolutely ideal for this quartet of plays in which the audience is asked to focus on

– even to share – the delusions of the five mad heroes. The plays are performed in a

repertoire of two double bills, with the same four actors taking all the roles. Each

double bill works on its own, but each will gain from being seen in conjunction with the

other. The double bills can be seen separately and in either order, although it’s

recommended to see Venus at Broadmoor and The Demon Box first. On seven days during the

run, one can, as I did, see all four plays in a day: two in the afternoon, two in the

evening. It’s a demanding, but rewarding, experience. Venus at Broadmoor opens with a

tableau in which the three men stand as if in a picture, while a light, ethereal girl

moves among them, half-floating, half-dancing with an invisible partner. The cast remains

this way for perhaps ten or fifteen minutes as the audience files in to this tiny

auditorium. It’s an excellent way of luring us away from the 21st century, and the

pattern is repeated – with suitable variations – at the start of each of the

four plays. Venus at Broadmoor, the story of

the ‘Chocolate Cream Poisoner’ Christiana Edmunds… is engaging in its own

way. There are some delightful moments… particularly the point at which actor Chris

Donnelly moves seamlessly from playing John Coleman, Principal Attendant on the

Gentlemen’s Block, into portraying four year old Sidney Barker, soon-to-be-victim of

those poisoned chocolate creams: instantly believable. Donnelly, as Coleman, is the

character who links the four plays together: part-narrator, part-cast, full of his own

doubts and difficulties. His consistency, his solid down-to-earthness, is welcome, and

grounding in a play in which so much cannot be trusted, and in which more than one of the

contributors turn out to be ghosts or figments of someone else’s imagination. The Demon Box, the second of this

pairing, works really well. Chris Bianchi, as painter Richard Dadd, is endearing and

appealing. I wanted to protect him from the demands of the other inmates and the casual

brutality of the staff. The dismantling of layers of convention made this play both

shocking and sad. The Murder Club, the first of the

evening’s double bill, has a great sense of menace and a marvellous swell of music.

Violet Ryder’s role consisted (as it did for a lot of the evening) of drifting

ethereally, but her ability to inhabit each part and make different that which could be

similar is impressive. She has a great sense of pace, and a great command of a lovely

voice. An actress to watch for the future. The thin division between sanity

and madness is very close to the surface in The Murder Club – and the shocking lack

of professionalism makes one realise how very badly the mentally ill were treated. Talk of

the war in Wilderness, the evening’s

final offering, is both powerful and moving. Madness here seems a perfectly sane response.

This is the story of William Chester Minor, one time surgeon in the American Union Army

and a major contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary during his time at Broadmoor. His

account of his experiences on the battlefields of the American Civil War makes madness

seem an eminently sane response. For a sequence that has madness and

murder at its heart, there is a surprising amount of humour throughout, from the witty to

the earthy. There are strong home truths and powerful performances… it does what

theatre should: it’s demanding, challenging, absorbing and entertaining. Small scale

theatre at its large scale best. By Jemma Bicknell and Greg

Battarbee Lullabies of Broadmoor is a quartet

of linked historical tragicomedies, revisiting the true stories of some of Broadmoor

prison’s most notorious inmates in the 19th century. Writer Steve Hennessy’s

background in mental health work permeates in these plays; they have a respectful

inquisitiveness, without pussy-footing around some of the thorny issues concerned in

detaining the mentally ill, that are as pertinent now as back then. In Venus at Broadmoor we are

absorbed into the story of Christiana Edmunds, the so called ‘Chocolate cream

poisoner’. The snug layout of the Finborough Theatre means we were immediately drawn

into the preoccupations of the characters even before finding our seats. The play started

with a fast paced account leading up to Christiana’s immurement. The cast freely

adopted various characterisations in the telling of the story in this part, yet the

narrative remained vivid. Later, the atmosphere changed

within the claustrophobic four walls of Broadmoor, and the space contracted, reflected

well in the simple staging. While Dr Orange sought to find a cure for madness and John

Coleman, the prison guard, wrestled with his own problems, the play explored individual

responsibility within institutions, and the blurring between obsessive love and madness.

This led us to dismantle some of our distinctions between the kept and the keepers. The next play, The Demon Box, was a

very well choreographed piece of theatre, in terms of movement, but also in how the

dialogue bounced between the actors, and how a simple turn or change in light could

effectively create a completely new scene, and then just as quickly skip back to the last

one. Richard Dadd was the central figure here, a compulsive painter who at an early age

savagely killed his father, believing him to be a demon. Chris Donnelly again plays the

prison guard very well, growing ever more despondent and dependant on his secret whisky

flask. Violet Ryder’s movement as the Puck-like Ariel was particularly lovely, her

delicate hands whisking up spectres and her body sinking cunningly into the background at

opportune moments. The most convincingly played

character was Richard Dadd, played by Chris Bianchi; he gently captured the alternate

sides of Dadd’s madness; far away, lost in the minute details of his painting, and

then the fluctuation between angry and whimpering that can be characteristic of long-term

mental illness. In this play, as in its

predecessor, the illness is explained in part by the characters’ decent into a

complex and archaic mish mash of ancient classical tales, this time from Egypt… it was illuminating to see their inner demons portrayed in flesh, and

chilling how believable it was that those patients could become slaves to them. by

Louise Kingsley These

four hour-long plays set in With

a background working in mental health, dipping into Broadmoor’s historic archive must

have proved as irresistible to him as were the strychnine-laced chocolate creams which resulted in the death of a 4

year old boy in 1871. Christiana

Edmunds, the young Brighton woman responsible, is the focus of Venus at Broadmoor (the

first of the quartet, though the most recently

written) and whilst never condoning her crime, Hennessy sets out the background to her

ultimately fatal poisoning spree – an affair with a married doctor – with

compassion. The

Demon Box constructs an imaginary meeting between patricidal painter Richard Dadd and

former American Civil War surgeon William Chester Minor, whilst The Murder Club brings

together the two least sympathetic characters – a jealous actor who stabbed his more

successful former benefactor and a conman who killed a prostitute in this very road. Finally

and most intriguingly, Wilderness (the original play, dating from 2002) returns to the

case of Chester Minor – the childhood and wartime experiences which shaped him, his

repentant relationship with his victim’s widow and, unexpectedly, his substantial

contribution to the Oxford English Dictionary during his years spent incarcerated in the

comparative comfort of the “Gentleman’s Wing” of the hospital. Four

actors do a sterling job tackling all the roles, with Violet Ryder particularly

convincing...Hennessy makes it clear that the criminally insane can, on occasion, be

victims as well as perpetrators. EDINBURGH REVIEWSLullabies

of Broadmoor Quartet: Fringe Review - Informed Edinburgh

|

|

Chris Bianchi – Dr. Orange in Venus at Broadmoor, Richard Dadd

in The Demon Box, Ronald True in

The Murder Club, George Merrett in Wilderness

|

|

| Chris Courtenay – Dr. Beard in Venus at

Broadmoor, Dr. William Chester Minor in The Demon Box & Wilderness, Richard Prince in

The Murder Club Chris trained at Arts Ed. Theatre includes A Christmas Carol (Trafalgar Studios), Henry VIII (Shakespeare’s Globe), The New Morality, Wilderness, The Murder Club (Finborough Theatre), The Master and Margarita, Akhmatova’s Salted Herring (Menier Chocolate Factory), Romeo and Juliet (Jermyn Street Theatre), The Dybbuk (King’s Head Theatre), Fallen Angels (Vienna’s English Theatre), Julius Caesar (Leptis Magna), The Blue Room (Tabard Theatre), Rumplestiltskin and Other Grizzly Tales (Wimbledon Studio Theatre), The Public Eye (Etcetera Theatre) and Macbeth, Hamlet (Cambridge Shakespeare Festival). TV, Film and Radio includes The Chilcot Enquiry, Royal Wealth, Alice and Camilla, Credo, Déjà Vu, The Furred Man, The Bed Guy, and Thor Heyerdahl in BBC Radio 4’s A Thor in One’s Side. |

|

Chris Donnelly – John Coleman |

|

Violet Ryder – Christiana Edmunds in Venus at Broadmoor, Ariel

in The Demon Box, Olive Young in The Murder Club, Eliza Merrett in Wilderness |

| Production Team: Director – Chris

Loveless Chris trained at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. He is Artistic Director of Fallen Angel Theatre Company and an associate director of the White Bear Theatre and Stepping Out Theatre. Directing credits include: The Remains of the Day, (Evening Standard Critics’ Choice, Union Theatre); Normal (Tobacco Factory); Moonshadow (Time Out Critics’ Choice and Show of the Week), The Custom of the Country (Time Out Critics’ Choice) and Dracula (all White Bear Theatre); Venus at Broadmoor, Vampire Nights, Ray Collins Dies On Stage, Walter’s Monkey and Thursday Coma (all Alma Tavern Theatre, Bristol); Stairway to Heaven (nominated for the Off West End Theatre Award for Best Director, Blue Elephant Theatre); Blavatsky's Tower (Brockley Jack Theatre); The 24 Hour Plays (Ustinov Studio). |

| Playwright – Steve Hennessy Steve has had twenty-one plays staged throughout the UK including Bristol, London, as well as four radio plays broadcast in the UK and Ireland. He was Playwright-in-Residence at the Finborough Theatre from 2004 to 2007 where the first two plays in the quartet – The Murder Club and Wilderness – were produced in 2004. His play Still Life won the Venue Magazine Best New Play Award, and Moonshadow (2009) was a recent Time Out Critics’ Choice. |

| Designer – Ann Stiddard At the Finborough Theatre, Ann designed Wilderness and The Murder Club (2004) and Viral Sutra (2006). Ann is a joint Artistic Director of Theatre West who have been a leading company for new writing in the South West for the last twenty years. She has designed dozens of productions for them at the Alma Tavern, Bristol. Other work includes The Two Noble Kinsmen, Shang-a-Lang, Blue Heart, Far Away (Bristol Old Vic), Little Pictures (Bristol Old Vic and Tour of Latvia), Six Beckett Pieces (Tour of Latvia), A Doll’s House (QEH, Bristol) and many productions for the Edinburgh Festival. She has designed all of Stepping Out’s productions for the last ten years. |

| Lighting Design – Tim Bartlett At the Finborough Theatre, Tim designed the lighting for Wilderness and The Murder Club (2004).Tim has designed lighting for dozens of productions for Theatre West, Stepping Out Theatre and other Bristol companies. His work includes Ray Collins Dies On Stage, The Vagina Monologues (Alma Tavern, Bristol) and Seven Go Mad in Thebes! (QEH, Bristol). |

| Costume Designer – Rebecca Sellors Rebecca has worked for over six years in the industry, designing and making costumes for television, film and theatre including several years at Angels Costumiers. Her work includes Bond Girls, Play Time, Venus at Broadmoor (Alma Tavern, Bristol), Chicago (DET NY Theatre), The Airmen and the Headhunters (Icon Film) and In This Style (Hollow Tree Pictures). |

| Producer – Stepping Out Theatre Founded in 1997, and with 35 productions to its credit, Stepping Out

Theatre is the country’s leading mental health theatre group. It has produced a wide

range of work on mental health themes and is open to people who have used mental health

services and their supporters. It offers mental health service users the opportunity to

work alongside people with professional experience of writing, directing and acting, some

of whom are service users themselves. The group has won two national awards in recognition

of its high quality and groundbreaking work in mental health. www.steppingouttheatre.co.uk |

| Producer – Simon James Collier Simon has worked for The Walt Disney Company and as an Entertainment Correspondent for the BBC. He has produced and been the Creative Director on over fifty plays and musicals including Great Balls Of Fire (Cambridge Theatre), Preacherosity, My Matisse (Jermyn Street Theatre), Shiny Happy People with Victoria Wood (Queen’s Theatre, Hornchurch), Passion, Purlie (Bridewell Theatre), Whole Lotta Shakin’ (Belgrade Theatre, Coventry), Elegies For Angels, Punks and Raging Queens (Bridewell Theatre, Globe Centre and Three Mills), La Vie En Rose (King’s Head Theatre and Towngate Theatre, Basildon), Normal (The Tobacco Factory), The Smilin’ State, Collision (Hackney Empire), Hedwig and The Angry Inch (K52 Theatre, Frankfurt), A Mother Speaks (Hackney Empire, New Wolsey Theatre, Ipswich and The Drum, Birmingham), Ruthless (Stratford Circus) and Dracula (White Bear Theatre). Simon recently produced Dance With Me, his first feature film. He has also been the Executive Director of London’s Bridewell Theatre and Artistic Consultant to Jermyn Street Theatre. |

| Costume – Penn O’Gara Sound Design – Hoxa Sound Movement Director - Cheryl Douglas Fight Director - Chris Donnelly |

| The Press on The Murder Club and Wilderness,

the first two plays in the quartet, performed at the Finborough Theatre in 2004 “Powerfully performed…by the same set of actors, the dramas are

like distorted images of each other, as they juggle with issues such as responsibility and

redemption and the relationship between illegitimate individual acts of murder and

publicly sanctioned mass killing. The result is a piquant mix of witty Gothic ghoulishness

and serious moral questioning... absorbing and atmospheric” “This macabre, grisly, but often funny double bill grabs the

audience by the dramatic throat and hardly lets go for more than two hours…the

psychological carnage is left behind long after the blood has been hosed away...every

character is created with care and finely executed...a consistently interesting, though

harrowing evening.” "Tragi-comic, black humour leavens these sad stories

...Multi-layered, clever, compact, yet ranging widely, Lullabies of Broadmoor demonstrates

sensitive writing…Hennessy has written and produced a gem as part of the

Finborough’s writers–in–residence season." “A double bill of plays that remind you why intimate fringe

venues can touch parts other theatres can't. The Murder Club, is a rumination on the

glamorisation of murder, the public’s lust for gory details and the mass murders that

go unpunished (and unreported) on the other side of the world. Set in 1922, Hennessy has

intelligently woven in, as backdrop, the British Commission in Iraq...the play is a

thought-provoking piece, directed with fluidity and poise in a restricted space. In the

final minute it swiftly shifts from its established delicacy of manner to a visceral

wrenching; bringing form and content into focus to make a very powerful end." "Steve Hennessy’s entertaining script revels in macabre

surrealism tempered by shrewd psychology and historical research …Drawing on real

cases, Hennessy weaves an ornate tapestry of emotional manipulation…Such is the

fertility of Hennessy’s mind that his shadowy gothic world compels you to keep

watching." “This isn’t a musty period drama or a whodunnit, but a

no-holds-barred assault on our moral and sexual conventions, our assumptions about sanity

and madness and on a society that claims to be civilised, yet seems to thrive on war

… Hennessy has done an outstanding job of using this macabre true story of

‘moral insanity’, murder and sex to lay bare the hypocrisy of our own tormented

society." “Darkly funny…frequently disturbing…a combination

of acute psychological insight and political and historical breadth …A rich mix of

characters and themes” “No doubting the quality both of writing and construction in

Steve Hennessy’s double-bill; his characters resonate in the mind the morning after

....Hennessy has a flair for visual moments that summarise character and writes

satisfyingly gritty, fluent dialogue... The Finborough has searched out yet another

individual theatre voice from whom we ought to hear more. |

Performances at the Finborough Theatre

Lullabies of Broadmoor - Finborough Theatre Tickets

Transport information - Lullabies of Broadmoor at the Finborough Theatre

Venue Finborough: The four linked plays of 'Lullabies of Broadmoor' can be seen together for the first time. They weave together the stories of five of Broadmoor’s most notorious inmates of the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the stories of those they murdered.

|

| Chris Loveless |